Honoring Our Marine Corps Warriors

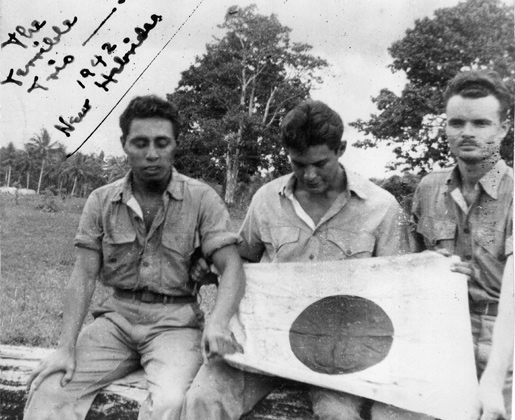

Santa Barbara Chocolate is a supporter of Veterans and Veteran's rights and a sponsor of The Eugene A. Obregon Medal of Honor Monument . The story below is by a long time chocolate advisor of ours, former Marine Raider, William Douglas Lansford. William (Bill) was in The Battle at Asemana on November 11 (Veterans Day) many years ago and wrote his account. We feel it is appropriate to submit this story because today is Veterans Day and as Americans we owe much to these brave individuals who have served and are serving our country. The story below was written at a time much different then today so it is filled with the colloquial language of the day as told by a warrior of the time.

William D. Lansford (Center)

William D. Lansford (Center)

THE BATTLE AT ASEMANA

By

William Douglas Lansford

Near dawn of 4 November, 1942, under a pouring rain, Companies C and E of the Second Marine Raider Battalion, under Lt. Col. Evans F. Carlson, landed at Aola Bay in eastern Guadalcanal. Their mission was insignificant. They would establish a beachhead for a detachment of Seabees who were to build an airfield. The Raiders would then turn security over to a battalion of the Army’s 147th Infantry Regiment and sail back to their base in Espiritu Santo. Their involvement would last 2 days.

Famous for their raid on Makin Island, Carlson’s Raiders had tried, unsuccessfully, to join the fighting on Guadalcanal, but Washington wisdom had it that the time for hit-and-run operations was over.

A Yankee preacher’s son, an Emersonian philosopher and an astute tactician, Carlson believed in Providence and Providence had seldom failed him.

The following morning, as the Raiders prepared to board their two destroyers, an American plane dropped a message for Carlson. On the same night the Raiders had arrived, a new Japanese force of 1,500 infantrymen, reinforced by artillery, had landed at Koli Point, a short distance west of Aola Bay. Next morning, they’d joined remnants of a Japanese brigade retreating from the last attack on Henderson Field. If they moved inland, a large enemy force would be loose in the jungle, behind the 1st Division’s already thin-spread perimeter. General Vandegrift was concerned. He wanted Carlson to find out what the hell was going on…

* * * * *

We’re a whole battalion again. Yesterday, Companies B, D and F landed at Tasemboko and moved inland to join us at our new base camp at Binu. We’re 4 days march out of Aola Bay, and 10 November being our Corps’ 167

th birthday, we celebrated with boiled rice, raisins and a canteen cup of black tea.

Around our fires we sang Raider songs, retold moldy, old sea stories, and amid yells of

“Gung Ho!” (while our corpsmen popped our blisters and handed out pills for malaria, drizzles, and jungle crud) we toasted the Old Corps with tea. And, as always, we men and officers were of a single heart in that damp, chilly evening, in the middle nowhere, in a village called Binu.

Next morning we started by changing socks, cleaning weapons and rolling our horseshoe packs for the march. The night’s rain had soaked our fires, so there was no warm chow. By the time the NCOs and Officers were briefed we’d gulped down our cold leftovers and here came Terrila, our skinny topkick, followed by Gunny McMurry yelling: “E Company! Off your ass and on your feet – we’re moving out!” It was always the same old crap, but it got us going, and if anybody bitched the guys yelled, “Hey, stupid! Who asked you to volunteer?”

The Colonel’s orders were brief: Company B would pull base camp security. C, D, E and F Companies would patrol north, between the Balasuna and Metapona Rivers, searching for the enemy force that had engaged Lt. Col. Hanneken’s 1/7 two nights earlier. Hanneken, who won the Medal of Honor in Haiti, told one of our patrols that the Jap unit they’d tangled with was at least a regiment reinforced by heavy mortars, machine guns and light artillery.

The enemy commander was determined and battle-wise. During the nightlong firefight he’d brought up his artillery and blasted Hanneken back across the Malimbu River. When Vandegrift sent a Battalion of the 167 th Army Regiment to assist Hanneken, the wily Nip found a hole in the Army’s line and by daylight 3,000 Japanese, with all their weapons and supplies, had disappeared into the jungle.

Carlson usually radioed 1 st Div Headquarters twice a day and briefed us through Gung Ho meetings in the field. At this moment, however, he knew little more than Vandegrift’s staff. Who the enemy commander was, what his mission and destination might be, remained a mystery.

Since leaving Aola Bay, the Colonel’s only sensings had come through SgtMaj Vouza’s Guadalcanal Constabulary scouts. For days they’d been reporting to John Mather, the Australian Army Major attached to Carlson’s staff, the presence of stragglers in the area. Mather, a tough , jungle-wise Aussie with a long scar down one side of his face, talked “pidgin” and translated for Carlson. Yesterday, guided by Vouza’s scouts, one of our patrols tracked and killed a Jap foraging party. But nobody knew where the main force was.

Having fought Sandino’s guerrillas in the Nicaraguan jungles and marched with Mao’s guerrillas against the Japanese, Evans Fordyce Carlson was at home in such tactic-blind situations. He’d organized and trained us precisely for unorthodox warfare, so he was confident we’d do the job when we met the enemy. Given the spirit displayed by Companies C and D at Midway during that epic battle and the aggressiveness of Companies A and B on Makin Island, Carlson had high expectations, even though Midway had been an air/sea battle and no Japanese infantry reached the beaches, while Makin was a raid against a tiny atoll that could be lost in any corner of the ’Canal.

Guadalcanal would be our acid test. For the first time, the Old Man had deployed our entire Battalion (5 Companies minus rear echelon) to test his tactics in terrain so wild that it was largely unknown, even to the coastal natives. The downside was that we’d be greatly outnumbered by an enemy considered the best bush fighters in the world, led by a Samurai who’d demonstrated a tiger’s claws and teeth.

E Company’s skipper was Capt. Richard Washburn, a six-foot-plus Yankee, easygoing and unshakeable. The guys called him “Jungle Jim” for his long stride and blondish good looks. Our Weapons Platoon Commander was Lt. Bob Burnette, a lean westerner who made Gary Cooper seem like a chatterbox. The guys called him Smiley. Like Washburn, Smiley was all of 25, but none of us would hesitate to follow him anywhere. Lt. Cleland (Tex) Early led E Company’s 2 nd Platoon to which our light machinegun section was attached. At 23, Tex was the “kid” among our officers, and like a kid, he was full of bounce and always spoiling for a fight. The 1st Platoon Commander was Lt. Evans Carlson, the Old Man’s son. Our NCOs were First Sergeant Rudolph Terrila, an aging veteran of the Banana Wars, and Gunnery Sgt. Edgar McMurry, dark, rawboned and solemnly silent. Our Platoon Sergeants were Earl Runyon, a stocky, good-natured Georgian, and Al “Ski” Kaminski, gentle but tough as a banyan tree. Nate Lipscomb was our Weapons Section Leader. All were old salts who’d served from Iceland to Shanghai and – as the old timers used to say – had “wrung more salt water from their socks” than most of us had sailed on.

But the wonder was Carlson. Twice the age of the average Raider, he could still outwalk, outthink, and outfight any man in the battalion. As proof of his faith, he had committed us to a hostile environment where no armies had ever gone; where we would operate alone, beyond hope of help or rescue. If our supplies ran out, if the jungle ground us down or the Japanese proved better soldiers, this trackless, unforgiving bush would be our tomb.

Everyone knew how Vandegrift’s sick, half-starved, ill-equipped Marines had fought for months and our admiration for them was boundless. I suppose what we really wanted was their acceptance for, beyond being Raiders, we were proud Marines. Soon we’d face starvation, sickness and death as they had, but we felt no fears. What sustained us was our belief in Carlson. He’d walked us in and when our mission was done he’d walk us out.

This morning, as the sun spread over the sky like a flaming disk, a sense of excitement pervaded Binu Village. We shouldered our packs and weapons, and at a signal from Washburn, stepped off, single file, with our native guides setting an easy pace of 3-5 miles per hour, climbing over a razorback ridge, then descending into a vast field of yellow Kunai grass alive with insects buzzing under the scorching sun. Along the horizon spread a broad stand of jungle and approaching it, the companies began separating like the fingers of an opening hand, moving faster and farther until they disappeared from our sight.

Alone, Easy Company continued breasting the chest-high elephant grass and we had just swung west, to enter the jungle, when a rain of mortar fire came down on us, exploding just over our heads.

At 1000 hours, the Headquarters people at Binu began hearing explosions from the direction of the Metapona. Energized by the excitement felt at the start of any battle, Carlson’s staff was already at their maps when the TBX broke the suspense. It was Washburn reporting that our Company had evaded a mortar attack by plunging into the jungle, and was now on the east bank of the Metapona. From there he could hear mortar and small arms fire coming from C and D Companies’ sectors, east and west of us.

At 1010 hours, Lt. Lamb, C Company’s squat, aggressive 2 nd Platoon Commander, called in. C Company’s point had sprung an ambush and killed 25 Japanese. Three Raiders were dead and several wounded. Now the Company was scattered and pinned down by fierce enemy fire, along with the C.O., Capt. Thorne. Carlson tensed. It wouldn’t be long before the enemy Commander realized that a Marine force had invaded terrain the Japanese had always considered their own. Without the element of surprise, and with one Company neutralized and another unreported, the mission could be in jeopardy.

As Carlson considered the situation, Charlie Lamb called again. He’d located the Company mortars and was counter- shelling the Japanese. Meanwhile, the Fire Team leaders, on their own, had started withdrawing through the elephant grass to set up a defense around an abandoned plantation a half-mile away.

“Hold on, Charlie!” Carlson ordered. “Regroup and hold!”

With C Company in trouble, D Company unaccounted for, and Fox Company miles away on the coast near Tetere, Carlson’s only immediate hope was Easy Company. If Washburn could cross the Metapona and find a small trail that led to a village called Asemana, he might swing up behind the Japanese and surprise them. Meanwhile, one thing was certain: the Raiders had found the enemy and now they had a tiger by the tail.

Carlson considered one other slim hope: Capt. William (“Wild Bill”) Schwerin, the Fox Company Commander, was as impulsive as Washburn was prudent, as reckless as Washburn was careful. He was a brawler, a boozer, and often a pain in the ass. The two Commanders had but one trait in common: both were courageous and inspired leaders.

Carlson radioed Schwerin to cut short his patrol and double time back to base. The day was up for grabs. If Washburn made it to Asemana and Schwerin returned in time to reinforce C and D, the situation might tilt to the Raiders. If not, Carlson’s dream could die there and his cherished Raider concept would sink like a loose anchor plunging into a dark and bottomless sea.

For the men of Easy Company, time had lost meaning. For what seemed hours, we’d been running, gasping for air, sweat soaked, our minds reeling. Nobody talked but there was a wild look in everyone’s eyes and in the faces of the NCOs and officers. Twice the column halted while Vouza’s scouts went ahead; then they’d return and the column would again go racing through the jungle. We wondered where Washburn and Burnette and Tex Early were. We felt adrift, not knowing where we were going, what was happening. Voices kept yelling for us to move faster. As Raiders we’d been trained to carry abnormally heavy loads of ammo and weapons, but nothing had prepared us for this nightmare.

The jungle air seared our throats. Gulping from our canteens, soaking our steaming heads was no relief. Our packs stayed glued to our backs. Some guys looked so red I thought they’d have a stroke. We were so tired we couldn’t even bitch.

Suddenly firing broke out ahead; the rattle of Nambus, answered by BARs and

M-1s. Thunderous explosions began tearing the treetops around us, splinters and steel filling the air. Running faster than the enemy gunners could adjust, we evaded that shelling, as well.

Stretched like a mile-long snake, E Company wound and twisted through the jungle following the Metapona, a brown ribbon between slimy banks. Swollen by 3 nights of rain, its swirling waters engulfed us as we slid in. Every Raider carried a 10-foot rope, so the lead Squad tied itself together to steady us against the current.

By 1015 hours, the 1 st Platoon was across and jogging upriver with Company Headquarters and Burnette’s Weapons in trace, and Tex Early’s 2nd Platoon still crossing.

As Lt. Carlson’s First Squad entered Asemana, they saw several native huts along the riverbank. Cpl. Bobb, an affable Indian-faced Squad Leader, and Pfc. Bob Wilinski, a BAR man, looked into one. There was a Squad of Japanese asleep.

Leapfrogging them, the next Squad froze. Near a bend in the river dozens of bare-assed Japanese soldiers were frolicking in the water while an endless column of Infantrymen waded across with their weapons and gear on their heads.

It took only seconds for Carlson and Sergeant Runyon to envision the situation: while separate patrols were blocking C and D Companies elsewhere, the main Japanese force was quietly passing through Asemana, moving deeper into the jungle.

Inside the hut, Wilinski made a decision: turning his BAR sideways, he fired his full clip and an enemy squad died in their sleep.

Alerted by the firing, realizing what would follow, Carlson moved up his Platoon and attacked. In minutes, the river was red with blood and Japanese bodies.

As if the Raiders had kicked a beehive, the Japanese column recoiled, deployed and counterattacked. Under a cover of intense mortar fire, two Japanese Companies began working around the Raiders’ exposed flank. Realizing his danger, young Carlson immediately recalled his platoon and disappeared into the jungle.

Thinking they had driven off a stray patrol, the Japanese ceased firing and, with the single-mindedness of an ant column, resumed crossing the river.

Meanwhile, Early had reported to Washburn. Burnette was there and after a 3-way discussion, Washburn ordered Early to resume the attack.

Eager, jumping with excitement, Early deployed his 2 nd Platoon and opened fire, again catching the Japanese in mid-stream and renewing the slaughter. Robotic as before – perhaps confident of their superiority – the Japanese again counterattacked. Only this time their Infantry was supported by six heavy machineguns, Nambus, snipers, and seemingly every mortar they had on the opposite bank.

While Early was attacking, we weapons people lay on the forward slope of a small hill where we’d emerged from the jungle, watching what seemed like a war movie developing 300 yards below. In the scrubby clearing of the deserted village, green-clad Raiders maneuvered amid yells of “Gung ho!”, mortar bursts and the din of automatic fire. Dodging, zigzagging, hitting the deck, the Raiders fired at the brown-clad Japanese who continued rushing the Raiders, only to be cut down.

To increase his mobility – and because our mission was to patrol –Washburn had left our 60mm mortars in base camp; so his heaviest firepower was our machine guns and we expected to be called.

There were some good gunners here: Tex Corbin, Joe Auman, the Lang Brothers, and the guys in my squad. I could see guys shooting at a big banyan tree from which a Nambu kept firing back. Dozens of small firefights were erupting everywhere, as if the whole battle had evolved into a series of personal brawls, fought at distances of 20 to 30 yards. Those were my friends. I thought of Al Flores, my Chicano buddy; of Erv Kaplan and Van Landingham, our radiomen; of my pals, John Elliott and Jack (Rabbi) Johnstone and all the others, wondering who were still alive. Then Nate Lipscomb ran up yelling: “Burnette wants the guns! Let’s go! Follow me, on the double!” And down we ran into the mess we’d been watching.

Half a century later, in his brief account of Asemana, the late Col. Cleland (Tex) Early would clarify much of what happened:

“I deployed my platoon in an L-shaped defensive position,” he wrote, “anchored by two machine guns on the bank overlooking the river crossing and protecting the right flank from an attack… Sgt. Lipscomb got our MGs in operation and commencedfiring at the Japanese crossing the river… The Squads on the left front also took the Japanese under fire. In the vernacular – we caught them with their pants down.”

As we arrived, a lull fell on the field. Lipscomb ran along the riverbank pointing and yelling: “Lansford! Set up there! Corbin! Over here! The rest of you – let’s go!” As he led the last two Squads away, Corbin and I slammed our tripods on the riverbank, hitting the deck while our assistant gunners clamped the guns on. It was just like drill: tripod down, gun clamped, receiver up, ammo belt in, bolt back to feed a round into the chamber.

Across the river the silence continued. Were they watching? Had they gone? Were they sleeping? It seemed too damned easy. What the hell was going on?

The answer came fast. A bird tweeted across the river and a small banana tree behind us flew apart. Someone yelled: “Jesus Christ!” then every machine- gun bullet ever made in Tokyo flew over our heads like angry bees.

In a flash of silliness it occurred to me that it was November 11 th. Checking my wristwatch, it was exactly 11 a.m. With my face in the dirt, I yelled: “Why are they shooting? It’s Armistice Day! The war’s over!” Nobody seemed to think it was funny.

The Japanese had opened up with six Hotchkiss heavies, several Nambus and lots of snipers. I could hear the rattle of our own light 30s firing. Tex Corbin’s gun, next over, was very busy. Beyond that I couldn’t tell if it was Auman and Monte’s gun or the Lang Brothers, but they kept banging away. While the Nip mortars were giving everybody hell, the Infantry already on our side kept trying to infiltrate our flank. At some point Nate Lipscomb came back cautioning somebody to: “Take it easy, you’ll burn your barrel!” Who he was yelling at, I don’t know. Time had become noise and confusion. I only knew we’d been firing forever.

A little past 1300 hours Bill Schwerin led a panting, sweating Fox Company into Binu having made an incredible 3-hour run from Tetere.

If Carlson felt relief, he said nothing. Earlier, Washburn had radioed that Easy Company was engaging two reinforced Infantry Companies and holding its own. But the fate of C and D Companies was still a blank. Carlson told Schwerin to feed and rest his men and stand by to take the field again.

At 1500, Carlson had just alerted Wild Bill Schwerin for movement when Capt. McDowell, the Dog Company commander straggled into camp with 9 exhausted men and a horrendous story similar to Capt. Thorne’s.

That morning, as McDowell led his Company to Charlie Company’s assistance, they’d sprung an ambush. McDowell and his point were instantly cut off from the others, and only after hours of hard fighting was he able to pull out with the 9 men he’d brought back. He couldn’t say what happened to the rest of D Company. In his opinion, they’d been wiped out.

Capt. (later Major Gen.) Oscar Peatross described the scene:

“Carlson’s face flushed…I could see he was angry. However, he calmly asked Mac for the last known location of the company and, turning to me, directed that I take a platoon to that area and search for survivors.”

Peatross’ Company B patrol had barely cleared the Raider outposts when he spotted GySgt. George Schrier with Dog Company trailing behind him. They had 5 KIA and 3 WIA, but were otherwise intact. Following Peatross back, Schrier repeated his story to Carlson: When he couldn’t find McDowell, Schrier assembled his Company, picked up his dead and wounded, and headed for home.

Thanking Schrier, Carlson immediately ordered Schwerin to assemble his men. But before leaving, Carlson relieved Capt. McDowell. The new Dog Company Commander would be Capt. (later Maj. Gen.) Joe Griffith.

By 1630 Carlson had reached the site where he found a shaken Capt. Thorne with a Company that was still disordered, but would show plenty of fight in battles to come. Carlson ordered the pugnacious Schwerin into the jungle where, except for a few snipers, Fox Company met no resistance. Having prevented Company C from reaching Asemana, the Japanese had withdrawn. To make sure they wouldn’t return, Carlson radioed Henderson Field (Cactus) for an air strike on the site, then marched his Raiders back to Binu where he relieved Capt. Thorne of his command.

Listening to distant thunder, Carlson would have known Easy Company was still heavily engaged, but his worries had largely left him. Two of his captains had failed, but two had not. Both the day and the Raider concept had flowered in good hands and a more satisfying victory was yet to come.

By 1630 hours, the battle for Asemana was still escalating. With Burnette’s machineguns covering the river and Early’s Fire Groups holding the north side, where the Japanese already across were massing, their only hope of retaking the village was to cross farther downriver, then come up behind Easy Company in an extremely wide flanking movement. The enemy Commander had the numbers. But Washburn had his Fire Groups and Marines trained in guerrilla tactics the Japanese couldn’t match. The Japanese had fought with their usual ferocity, but their textbook tactics showed so little variation that nearly every move was predictable.

By now, we could all sense their mounting desperation. Repeatedly, they had attacked, run into a wall of Raider fire and pulled back with heavy casualties. In over 7 hours of fighting they’d been unable to break out of their jungle cover into the clearing we’d held since Tex Early’s attack.

But we, too, had paid a toll. We were exhausted, out of water, and almost out of ammunition. Our day had produced many oddities, close calls and tragedies.

Burnette had been observing from inside a hut, when he spotted the troublesome Nambu and motioned Early over. “Just as he pointed to it,” Early recalled, “…the gun opened up and literally chopped the hut down over our heads.”

Leaving Sgt. Kaminsky to hold the critical right flank, Early assembled an Attack Group consisting of Lipscomb, Pfc. Wilbur Whitaker (BAR), Pvt. Carl Cantrell (Thompson submachine gun) and Pvt. Edward Grejczik (M-1) and went after the Nambu in “one helluva skirmish. Each time we killed one gunner,” Early recalled, “another would take his place.”

Terrila was having his own adventures. Spotting a sniper behind a tree, the old bush fighter crept to the opposite side of the tree, poked his rifle barrel around and shot the sniper dead. Meanwhile, under heavy fire, Gunny McMurry kept chugging up and down our line, yelling, “Keep your ass down if you don’t want it shot off!”

Amid the confusion, Pfc. Flores, Washburn’s runner, kept hopping back and forth carrying rifle grenades so Early’s men could blast snipers out of the trees. Later he would earn a Silver Star in an action that earned Schwerin the Navy Cross.

Washburn had his “headquarters” in a shallow, bush-covered hole where Pvts. Erv Kaplan and Jesse Van Landingham kept grinding their TBX, under continuous mortar fire. Since mid-afternoon, Washburn had been unable to contact Col. Carlson or the other Companies, so he’d fought his battle without help, without even knowing the fate of the rest of the Command or, indeed, if the Battalion still existed. Quietly, calmly, without faltering, Dick Washburn would prove himself the most resourceful of Carlson’s Captains.

It was now 1700 hours and the Nambu had finally been silenced, but at a price: Whitaker, Cantrell and Grejczik had all been hit, although not seriously. Approaching it, Early found 6 dead gunners. The last man, a young Sergeant, was still at the gun.

As Early turned him over, he heard a puff. The gunner had died clutching a grenade in his hands. “I ran like hell,” recalled Early, “and received only a few pieces of shrapnel.”

Those defending the right flank weren’t as lucky. Joe Auman was killed by a bullet in the face after his machine gun jammed. Art Monte, his assistant gunner, was missing and the gun was in the river. While resisting the infiltrating Japs, Pfcs Jerrold Miller and Lorenzo Anderson were both shot by snipers. Miller, hit between the eyes, died instantly. Anderson, shot through the head, died before a Corpsman could reach him.

Earlier during the battle, Washburn had sent Lt. Carlson’s Platoon to reinforce Early. But now the rain of mortar fire that preceded every Japanese attack was intensifying. It was clear that the Japanese were going to make an all-out effort.

As the sun set, through the trees on the north side of the village we could see large groups of Japanese Infantrymen working their way around us. In minutes, we would be trapped between them and the river and by then it would be dark.

Aware of his Platoon’s condition and of the worsening situation, Early asked Washburn if Carlson’s Platoon could relieve his if they were to stay the night.

Washburn’s reply was short and sweet: “I think,” he said, “we better get the hell outta here.”

As Early’s Fire Groups covered us, we picked up our guns, moving back up the hill where we had entered. From there we could see Early and his guys firing, falling back, then turning to fire again, delaying the Japanese as the last of us emptied the field. They were beautiful!

Then I saw something I would remember all my life: It was Monte, coming out between two Raiders, limping, bloody, his helmet askew, but still defiant with a .45 in his hand. Wounded by the same sniper that killed Auman, Monte had pulled the backplate off their jammed machine gun, pushed the gun into the river and crawled under a bush from where he could see “hundreds of Japs moving into Asemana.” Seeing us withdrawing, he ran after us, his yells attracting two Raiders who went back to help him. They were the last out. In minutes Asemana was filled with Japanese. But the Raiders were gone.

Now we were running again, back the way we had come. Night had fallen and despite our weariness, we didn’t mind. It was good to be alive. Through the dark jungle we went and by 2200 hours we were safe in Binu.

Not until next day, when we returned to Asemana and buried our friends, would we understand the damage the Japanese had sustained. They’d gone with their wounded, but not before burying their dead – sometimes 3-deep, on both sides of the river – to hide their losses. It was the beginning of the end for Col. Shoji, his 230 th Infantry and the attached right wing of the Kawaguchi Brigade. Tomorrow Col. Carlson would lead us out again and for the rest of November through 4 December (during what would go down in Guadalcanal history as “The Long Patrol”) we would pursue and engage them, until by the time we reached Mt. Austin the Tiger and his once proud force had ceased to exist.

It would be the longest patrol in Marine Corps history and, in the opinion of Lt. Gen. Merrill Twining (then Gen. Vandegrift’s Operations Officer), the most perfectly planned and executed mission of the Guadalcanal campaign.

But that’s another story.